Man’s Best Friend, Cattleman’s Foe

In 1915 Alabama, a wealthy special interest group boosted their own profits and freedoms while binding dog owners to inequitable taxes, threats, and restrictions.

It is a pattern that has continued to the present day. Nevertheless, a 1915 law that took aim at dogs has become a key protection.

The Cattleman’s Scheme

Since the first attack, the cattleman loathed the coyotes and the dogs that harassed his livestock. The four-legged predators killed his calves and trotted off with his chickens. He could hold the owner liable, but sometimes the dog was wild or the owner indigent. He could aim the barrel, but the pesky canids kept coming. He could make an insurance claim, but he and the insurer alike preferred others to shell out. So he schemed to pad his pockets on another man’s dime:

What if dog owners were forced to pay for harm caused by every dog — whether owned, stray, or wild?

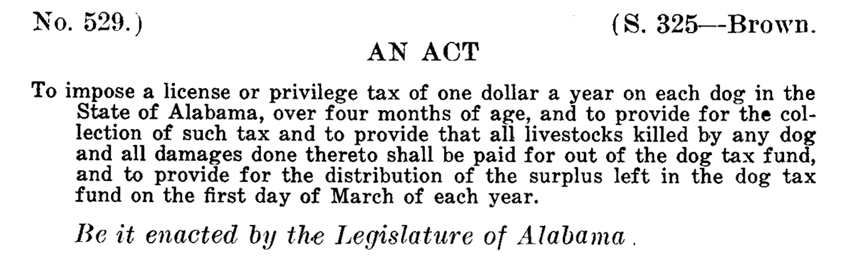

The man riled up his fellow cattlemen, who called in a favor for their contributions to state representatives. In 1915, legislators delivered:

Alabama legislators enacted a mandatory tax on dog ownership. This wasn’t the state’s first dog tax. Earlier dog taxes had been enacted in many counties and municipalities, and a statewide optional dog tax in 1887. Those taxes supported public schools.

The 1915 dog tax marked a major shift in that revenue exclusively benefited a special interest group, rather than funding a public program. Under the new law, dog tax revenue would be collected from dog owners and paid directly to livestock owners. The dog owner was already liable for harm done by his dog; now he was also required to insure the rancher against harm by wild dogs or dogs belonging to indigent owners.

The 1915 tax demanded $1 per dog annually, or something like $32 in today’s dollars. Many localities (Crenshaw, Dallas, Limestone, Madison, Morgan, Russell counties; Florence, Fort Payne, and others) charged the same or a higher rate.

Death or Taxes

Not that cattlemen were forcing dog owners to pay. Those who couldn’t pay or who objected to the tax had the alternative of giving up their dog to be killed. An MP’s characterization of a 1796 dog tax bill in England just as aptly described Alabama’s law:

Nothing less than a death-warrant to that valuable race of animals.

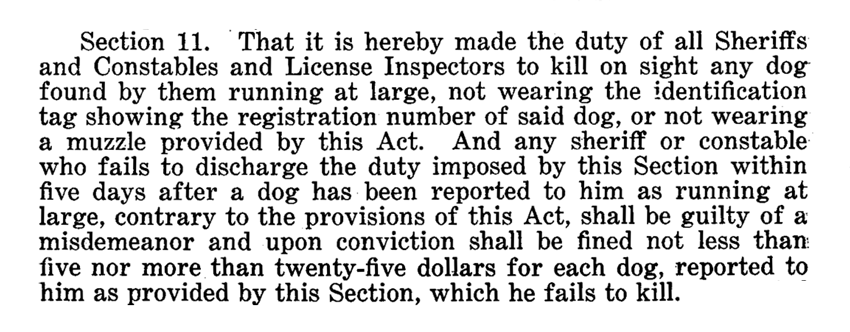

The dog tax statute demanded the immediate killing of dogs for whom no tax had been paid. Officers were compensated 50¢ per dog killed — and for each dog they “failed” to kill, charged with a misdemeanor and fined $5 to $25. This was state-mandated cruelty.

The cattleman’s assets were protected by law. Meanwhile, dog owners were threatened to hand over their money or risk the killing of their dog, a codified extortion.

Snooty Judgments

The dog tax required the owner to buy back his own possession. Further, it violated the understanding that the poor should be exempt from tax and that necessities should not be taxed. It is for this reason that legislators attempted to justify the tax by pretending that they were actually just trying to help poor dog owners.

They labeled it a “privilege tax,” a sumptuary law intended not to burden but to protect the poor, to wake him up from his foolish ways. After all, he who can deprive himself of food by keeping dogs is living in opulence; for such a man, taxation of his superfluous things is no burden. The taxes and other restrictions imposed on dog owners in 1915 represented an effort by the upper class to control and to take from the lower class.

(If cattlemen were actually concerned about food for all, they would end the enormously inefficient practice of converting land, water, and energy to cow flesh. It is beef that is the true luxury when its consumption of resources is considered.)

The classist view and judgment of the poor as unfit owners can be seen in a 1792 letter to Gentleman’s Magazine, as quoted in Lynn Festa’s study of England’s dog tax:

I hope the regulation of the tax will entirely prohibit all unqualified persons from keeping game dogs.

This attitude is still prevalent today, and can be seen in calls to punish the indigent pet owner rather than assist him, such as with accessible pet sterilization options.

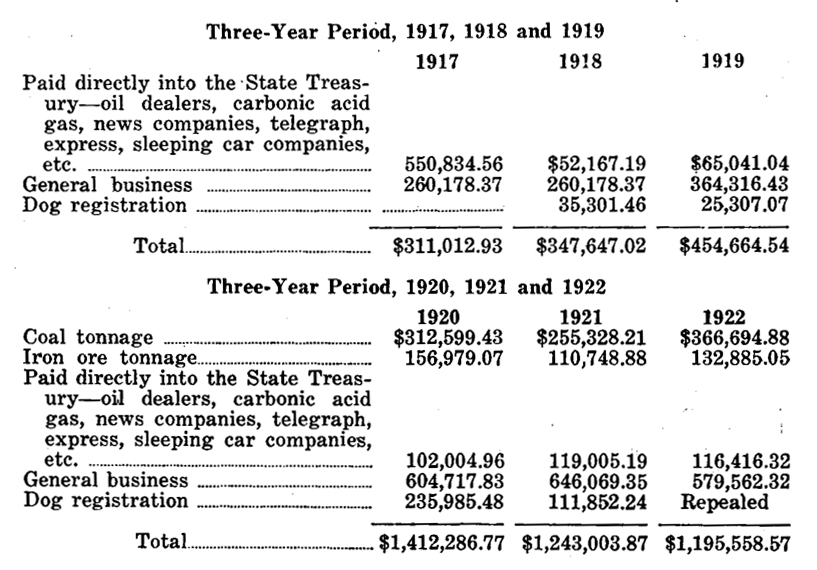

In Alabama as in England, the ruse of a dog tax as a fair or helpful requirement did not last long. Alabama’s 1915 “privilege tax” was presumably repealed by 1918 (records are not available); a 1919 revised dog tax was repealed in 1921 by a 72 to 15 landslide vote.

These repeals were part of a pattern throughout the US and England to end so-called luxury taxes on property not considered essential. Most of the once-abundant local dog taxes were also repealed: as a few of many examples, Fayette County taxed dogs from 1893 to 1896, Madison County from 1909 to 1915, and Russell County from 1907 to 1909.

Livestock Roam Free, But Confine Your Dogs

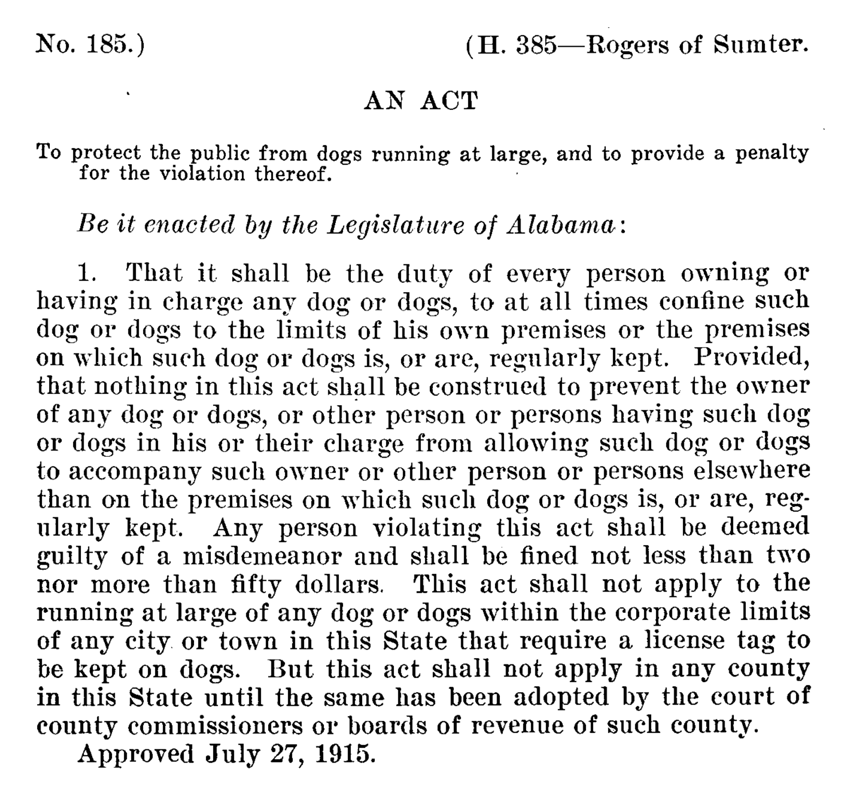

While the dog tax statutes ordered death to untaxed loose or wild dogs, Alabama’s Dogs Running At Large statute, also dating to 1915, fined taxpaying owners for allowing their dogs to leave the owner’s property.

Meanwhile, cattlemen largely eschewed personal responsibility for protecting their cattle from predators or cars. They needn’t even erect fences, since Alabama was an open range state that did not fully close until 1951. Livestock owners bore no responsibility for damage caused by farm animals to family gardens or farmers’ crops. Even today, owners are not liable if their cow in the road causes an accident. But loose dogs with no tax tag? They were ordered to die.

It was another inequitable law. The state’s prosperous cattlemen enjoyed all of the protection of the government and the financial support of his poorer neighbors while the everyday dog owner faced restrictions and fines. The combination of laws granted every wish to the rancher: death to most dogs, the siphoning of funds from owners of the remaining dogs, and restrictions and fines as threats to keep dogs confined.

A Repeating History of Protecting the Elite, Binding the Masses

As described above, in 1915 Alabama a wealthy special interest group boosted their own profits and freedoms while binding dog owners to inequitable taxes, threats, and restrictions. In 2025 Alabama, the pattern continues:

- Industrial-scale animal agriculture lobbies have blocked basic companion animal welfare legislation due to fears of a slippery slope leading to demands for more humane treatment of farmed animals. The Pet Protection Act, for example, faced years of opposition and passed only after being altered to protect only dogs and cats rather than all animals. Multiple attempts to legally define minimum requirements for shelter of outdoor dogs have failed at the hands of ALFA-funded legislators.

- When non-profit clinics offered high-volume, low-cost spay and neuter, an Alabama profit-driven vet group impeded operations by embroiling the clinics in years of legal challenges. AVMA, the American Veterinary Medical Association, and many private vets have since 1974 opposed low-cost sterilization, “balking at any real or imagined threat to business profits,” as described by Nathan Winograd in Redemption. The threats were, indeed, imagined: “With four clinics operating, private veterinarians were still performing 87% of all neutering within Los Angeles, because the clinics were being used by poor people who would not otherwise have had their pets altered,” Winograd wrote. Despite this, certain Alabama vets bulldogged two of the state’s critical non-profit clinics for a decade.

- Similarly, vet groups largely prevent shelters from simple and necessary medical care for animals such as administering rabies shots, injecting microchips in owned animals, having an in-house vet to administer fluids or sterilize animals, or offering veterinary services to the community. Their profiteering exacts a tremendous cost on Alabama taxpayers and is a direct cause of many of the challenges facing residents, shelters, animal control, and local governments throughout the state.

Economists Daron Acemoğlu and James Robinson warned of these sorts of policies in Why Nations Fail, winner of the 2024 Nobel Economics Prize:

The most common reason why nations fail today is because they have extractive institutions.

Extractive institutions extract wealth from society to benefit a select few. In Alabama, these self-serving attitudes are seen in the cattlemen willing to siphon funds from poor dog owners, the industrial ag operations at which horrific abuse is a daily occurrence, the profit-driven vets willing to prevent every inch of progress in this state to ensure that all business is funneled their way.

When will cooperation trump selfish profiteering? When will humane treatment be valued above exploitative capitalism?

From Restriction to Protection

One of the 1915 laws described above is still on the books today, and despite its original intent to restrict and penalize dog owners, today it is among Alabama’s most important laws for the protection of dogs and communities.

The prohibition on dogs running at large, § 3-1-5, promotes public safety and quality of life for people and dogs alike, while discouraging breeding and reducing government liability. It is a key measure amid a doubled state population and the accompanying busier roads and increased residential density.

However, its usefulness is limited due to its conditional application clause. Unlike nearly every other state law, § 3-1-5 applies only if adopted by the county commission. This condition was added to get the required votes in 1915, when county dog taxes were common. Today, the condition is a source of confusion, as detailed at Key Findings on Dogs-at-Large Laws, and is no longer relevant. In most of the state’s counties, the law is inapplicable, often because officials didn’t realize they needed to adopt, because no one requested its adoption, or because of misunderstandings about its enforcement.

Legislators now have the opportunity to improve quality of life and demonstrate a commitment to public safety by making the statute automatically applicable statewide.

—

Written by Kristin Yarbrough. Thanks to Lori Howell, Dustin Dutton, and Aubrie Kavanaugh for conversations that informed this research.