Dogs-at-Large Laws in Alabama

When we see dogs running loose, we tend to assume they are off of their own premises because the owner does not care or allowed the dog to roam. This is not always the case. Accidents happen. Children leave doors open, contractors leave gates opened, dogs jump fences (or dig out from under fences) and dogs flee when scared.

If you see a dog running loose, the owner may be looking the dog. Please follow the steps to assist animals who are lost, stray, or abandoned. Your efforts may help the dog return home. If you see a dog running loose repeatedly, it is possible the owner allows the dog to run loose or does little to prevent that from happening.

Alabama Dog Confinement Laws At a Glance

- Requirements: Confinement or ‘running at large’ laws stipulate that dogs be confined to the owner’s premises or kept in the charge of a responsible person if off-premises. Some municipal ordinances require that a physical fence and/or a leash be used; the state law (§ 3-1-5) does not.

- Applicability: Dog confinement is required in many or most Alabama municipalities and in the unincorporated area of 25% of Alabama’s counties (and in some or most municipalities). There is currently no requirement in ~75% of the state's unincorporated area. Easy options are available for counties and municipalities that wish to require confinement.

- Enforcement is possible even where there is no animal control, since it is typically the responsibility of the affected resident to document and report and to press charges if violations continue.

- Penalty upon conviction of the statute is a fine of up to $50 plus court costs. Municipal ordinances may carry higher fines and the possibility of imprisonment.

Applicability

Before we get into the technicalities, here’s the simple version:

- If you’re in a county that has adopted Alabama Code § 3-1-5, dog confinement is definitely required in the unincorporated area and typically required in every municipality as well. If a neighbor is allowing a dog to run loose, report.

- If you’re in the unincorporated area of a county that has not adopted the statute, there is no confinement requirement. There are still steps you can take to address issues or to encourage your county to require confinement.

- If you’re in the corporate limits of a municipality, your city or town may have its own confinement requirement.

Applicability: Technicalities

Here’s how to definitively determine whether dog confinement is required:

Does a municipal ordinance apply? First check Municode: scan through the Animals chapter for terms such as at large, off-premises, unrestrained, or running loose. If the municipality does not post its ordinances on Municode, call City Hall or Town Hall to ask. Whether or not the municipality requires confinement by ordinance, the state law may be applicable, as described next.

Does the state law apply? Alabama Code § 3-1-5 applies when both of the conditions set by § 3-1-5(b) are met:

- The County Commission has adopted the statute (check the map), and

- The location where the dog is allowed to run loose is an unincorporated area of said county or within a municipality that does not require license tags [an example of a license tag requirement can be seen at Oneonta § 3-31].

Our research has shown that in counties that adopt the statute, confinement is usually required in the entire county. This is because the statute covers the entire unincorporated area, and municipalities in which the statute is inapplicable tend to be covered by their own confinement ordinance.

In the absence of an applicable state or local law there is no confinement requirement, as established by the 1952 decision of the Alabama Supreme Court in Owen v. Hamson. See Advocacy for steps you can take.

Advocacy

While many people presume allowing a dog to roam doesn’t hurt anyone, that is not the case. Dogs running loose can cause car accidents, can lead to fights with other animals, may result in injury or death to another person, or may result in the dog being shot. It is incumbent on all of us to take extraordinary measures to keep dogs confined for the benefit of human and animal residents alike. If confinement is required at your location, do not hesitate to report violations.

If confinement is not required at your location, there are several steps you can take:

- Ask for a dog confinement law. Use this information to talk to your commissioner or councilmember.

- Talk to the dog owner. If you can safely do so, talk to the neighbor who allows his dog to run loose, or request that an animal control officer or law enforcement officer speak to the neighbor.

- If the owner allows the dog to roam while not wearing a current rabies tag, request impoundment.

- Hold the owner responsible for livestock harmed or killed by his loose dog.

- Other possible recourses include nuisance law or municipal noise ordinances.

Officials and residents who would like a confinement requirement can reference Guide for Counties & Municipalities for how a requirement can help, impacts on local government and law enforcement, considerations prior to adopting, and discussion of common concerns and misconceptions.

Enforcement

Enforcement of at-large laws is prompted by a resident’s report or an officer’s witnessing of a dog running loose. Enforcement may be handled by a ACO, another law enforcement officer, or an appointed agent. A responding officer or agent may address the situation in a variety of ways:

- Warn the dog owner that he must comply with the law. This is typically done in person, though some counties and municipalities mail a letter instead.

- Issue a citation if the dog is off-premises in the presence of the officer, if the dog owner can be identified, and if the officer has citation authority. The officer may submit bodycam footage as evidence of the violation.

- Impound the dog, if the dog is off-premises. (The dog owner may subsequently reclaim by paying penalties and fees.)

If no citation is issued and/or violations continue, the resident can ask whether the agency or official will address the situation again. The resident also has the option of bringing evidence directly to the court. This is known in Alabama law as a complaint, though we more commonly hear it referred to as “pressing charges” or “swearing out a warrant.”

If the magistrate or judge finds sufficient evidence of a violation, the dog owner will be summoned to court and will have the opportunity to plea or to contest the charge.

Penalties

Violation of Alabama’s confinement statute is a misdemeanor which carries a fine of $2 to $50, plus locally-determined court costs. The range of court costs that we are aware of is from $175 to $332.

Generally, violation of municipal laws carries a more severe penalty than the state law’s $2 to $50 (which, when established in 1915, was equivalent to $60 to $1500 in today’s dollars).

License Tags

The “license tag” exception in the At-Large statute's second paragraph [Alabama Code § 3-1-5(b)] refers to a tag issued upon registration or licensing of a dog. Mandatory licensing was common in Alabama when this law was enacted in 1915 but is uncommon now, so this reference can be confusing.

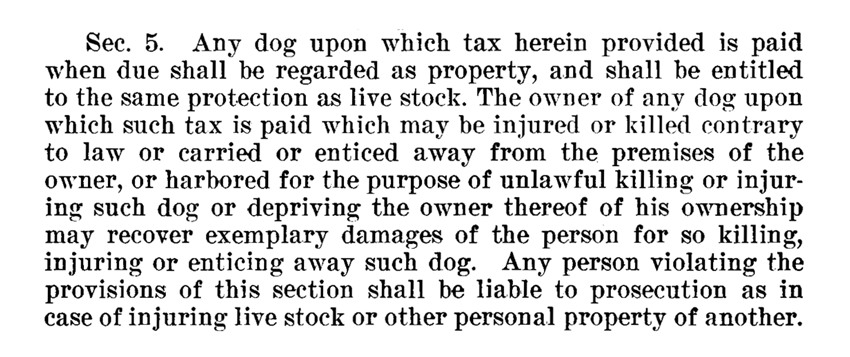

In late 1800s and early 1900s Alabama, many counties and municipalities issued license tags to mark paid-for dogs. Just as a car license plate (“tag”) indicates that the car is registered, taxes paid, and “given privilege or free range,” the 1919 dog tax statute specified that “a suitable metal tag” be issued and then worn by the dog. The statute ordered officials “to kill on sight any dog found by them running at large, not wearing the identification tag showing the registration number.”

Today, it is illegal to harm kill a dog for merely running at large, with or without a license tag (though unfortunately, we commonly hear that some officials advise residents to shoot loose dogs).

—

A Note About Word Choice: These laws are often called ‘running at large,’ ‘leash laws,’ or ‘containment laws.’ The first is from the name of the statute, Permitting Dogs to Run at Large. ‘Leash law’ is a misnomer for the statute, which makes no mention of leashing.

We prefer the term ‘confinement’ rather than ‘containment’ because a) ‘confine’ is the term used in the statute, and b) ‘contain’ can skew toward restricting something hazardous whereas ‘confine’ is usually defined more neutrally, e.g., simply to enclose within boundaries. Extremely few dogs are dangerous: only 0.01% of dogs (or roughly 1 in 10,000) bite with enough force to cause an injury, according to Nathan Winograd, and the percentage of truly aggressive dogs is perhaps a quarter of 1%. Thus, the neutral term more accurately represents the function of such laws.